With apologies to Paul McCartney, for some time now I've been aware of the distinctive tone, player selection and look Topps used for some of their high number series from the 1950's. With the baseball season in full swing, On a macro basis I would estimate June was the month the highs were created and composed in most years, so what better way to kick of the portal to summer?!

1952 is, of course, the most famous high number series of them all. I've expounded on it almost ad nauseum over the years (click over to the labels if you don't believe me), and don't feel the need to address much more of it here. Created after Topps thought they would stop their inaugural Baseball issue at 310 cards, or so the story goes, it's the biggest series of the set at 97 subjects and contains three famous double prints. My own opinion as to the greenlighting of this last batch is they finally signed Mickey Mantle, Jackie Robinson and host of Dodgers after prior contracts finally ran out in mid-June. Whether due to a need to shunt three cards of managers to the fifth series, leaving a lack of players or coaches to fill in that small gap left by such a move, they came up short and had to double up Mantle, Robinson and Bobby Thomson in a series also loaded with no-name rookies. Truly a "prince and pauper" series if there ever was one.

Generally referred to at Topps in 1952 as the "second series", its lackluster sales seems to have tempered their thinking about the length of their sets over the next half a decade. Here is a good example of how Topps used coaches and managers to fill out the series. There's 11 of the former and 3 of the latter among the 97 subjects. The entire Dodgers staff was present: Manager Dressen, and coaches Lavagetto, Herman and Pitler.

In fact, if you look at the New York teams, they have a combined 35 subjects represented in the highs, with 9 of them managers or coaches. That left 57 slots for players, coaches and managers from other teams. Take away 14 Boston Braves and Red Sox subjects (Beantown was seemingly the next biggest market in 1952), there's only 43 numbers left for ten teams (no White Sox made the cut). Here's Pitler:

1953 brought a smaller set, planned to have run 280 cards. except that six subjects were withdrawn due to their exclusive deals with Bowman. My thought is Topps left holes in the earlier series (such as the five missing numbers in the 1st series), which they then "backfilled" from the next to allow for this. The first series was missing card nos. 10, 44, 61, 72 and 81 and when those were printed with the second series, they likewise likewise held back nos. 94, 107, 131, 145 and 156. Those were printed with the third series, which was otherwise 55 cards in length. Ending at #220, maybe Topps briefly thought they were out of the woods with Bowman or even done for the year, but they most certainly were not as nos. 253, 261, 267, 268, 271 and 275 never appeared.

There is some star power in the 1953 high numbers, with Willie Mays and Jackie Jensen present but it's the gaps that define the highs.

1954 doesn't really have high numbers as the set was printed in an odd fashion, with seeming huge numbering gaps in the later series press runs (and possibly the first series), suggesting some pessimism at Brooklyn HQ. In addition, there weren't enough subjects in the set to extend into true high number territory. There is a second Ted Williams card though, concluding the set at #250, which is a nice bookend to the #1 card he leads off the set with.

Topps did do something special with this card though, using a Brady Bunch-ish motif for the cartoons and a note to check card #1 in the set for the Splinter's stats:

1955 saw the shortest set of the era for Topps, when 206 out of a planned 210 cards were issued. There's some weirdness to the print arrays for the first series, where some holes seem to have been created, just like in '53. At the end, four numbers were pulled: 175, 186, 203 and 209, as Topps continued to wrangle with Bowman. It's been suggested in the big Beckett Almanac of Baseball Cards & Collectibles that nos. 170 (Pearce), 172 (Baumholtz), 184 (Perkowski) & 188 (Silvera) were double printed to replace the missing cards on the press sheet. There's really no distinction of a high number series this year either and the distribution of stars is robust from nos. 161-210.

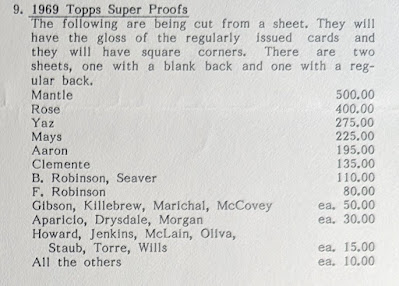

1956 was the first year Topps didn't have to compete with Bowman, having bought out their erstwhile competitor in February. To me that means at least one if not two series were already planned at the time of the sale and it's possible they took a wait and see approach at Topps, planning to definitely issue 260 cards before committing to the final 80. They certainly truncated the Baseball Buttons set at 60 pins, 30 short of the intended (and announced) number.

Two things stand out in the 1956 high numbers, Wesley Morse, of Bazooka Joe fame, did all the cartoons from nos. 261-340 (he didn't do any of the first 260) and there are no team cards, which debuted as a feature in series one, as Topps concluded those at no. 251 with the Yankees and issued them for all sixteen teams before they got to the last series. Finally unencumbered by Bowman's contracts, Topps also started "pushing" unnumbered checklist cards into the packs for the first time in 1956, one checklist covered series 1 and 3, the other series 2 and 4. I would very much like to understand the timing of their insertion as I suspect it could have been quite late in the production cycle.

Check out the bottom text on the 2/4 checklist:

It's almost like they wedged in the "340" isn't it? I wonder if they had a different number in mind originally.

1957 gives us an anomaly, with the toughest cards being in the semi-high series 4 and running from #265-352. The highs end at #407 and are pretty much a wasteland of established major league talent, although Topps did add two extremely nice, high octane multi-player cards at #400 (Dodgers' Sluggers) and #407 (Yankees' Power Hitters) to round things out. I suspect this final series was a test of sorts, to see how many cards could realistically be produced with sixteen teams. If you take away the team cards, and the multi-players cards (plus the League Presidents card) you get an average of a little over 24 players per team, so Topps was at the extreme limits of what was possible given the rosters of the day.

Topps also pushed four standalone checklist cards (and some contest cards printed with them) for each series in the packs. Each checklist covered two complete series (1/2, 2/3, 3/4 and 4/5). Once again, there are no team cards in the last series. I have to think they knew by the time the second series was issued in any given year if they were going to put out a final series.

This isn't a card but rather a paper proof of the Dodgers' Sluggers:

1958 saw a new innovation, the team cards had checklists on their backs. Topps clearly saw a path to issuing more cards as 494 of a planned 495 subjects hit the streets, with #145 pulled due to the January 17 arrest of the Phillies Ed Bouchee for indecent exposure in Spokane, Washington. (Bouchee was convicted on March 7th, given three years of probation and suspended by Commissioner Ford Frick, pending psychiatric evaluation and finally returned to the Phillies in early July). Bouchee was replaced on the second series press sheet by Jim Bunning.

A large number of multi-player cards were issued by Topps in 1958 and they also stretched things out with an All Star subset (their first) with the in-season signing of Stan Musial giving them something to crow about (he got an AS card but no regular issue slot). Once again, no team cards were created for the last series of the year.

If you look at the high numbers in '58 they otherwise feature a parade of nobodies and rookies as Topps seemingly intended to tentatively stop production at 440 cards before deciding to issue the final series. We can tell because the team cards held the checklists for the first time and only the last four came as "two-ways", where you could find either a numerical or alphabetical version on the backs of the Braves (#377), Tigers (#397), Orioles (#408) and Redlegs (#428) cards. Earlier team cards only had the numerical checklists.

I've shown these four variants previously, but look at the back of the Braves team card. The alphabetical version caps out at #440 (we can confirm this because #474, the last "regular" card in the set, is of Roman Semproch, who is not found here on the "Fourth of 4 Cards" in the alphabetical sequence:

So, not "any" player could actually be located, as we see on the numerical version of the card:

It seems Topps was awaiting the final All Star Game rosters from Sport when this card came out, doesn't it? I have to think the changing of the major league map was testing Topps in a way, especially with the two NL teams from New York relocating to California. It seems like they were feeling their way through a somewhat unfamiliar landscape. By the way, to get to 21, there were All Star cards for lefthanded and righthanded pitchers from each league and a manager's card with both Stengel and Haney.

1959 was a little more organized as Topps seems to have planned for a longer release from the get-go. The checklists don't really tell the story for the 1959 highs but the card backs sure do. Here's a lower series card reverse from '59:

Meanwhile, for the 7th series, we get this:

All the green's turned black! And, we also get team cards in the high numbers:

As an aside, this particular can be found centered reasonably well on one side or the other but not necessarily both:

I assume the west coast sales from 1958 allowed this more reasoned approach in 1959. Plus the highs looks much sharper than what came before them.

1960 brings us a trio of "lasts": it's the final year of the decade (yes, it's true), the last year of the team cards holding the checklists and, certainly not least, the last year of sixteen major league squads. Each series through the fifth is identifiable by variations in the cardboard stock but then another "last" was realized, namely a seventh series, although it was indistinguishable from the sixth in terms of cardboard stock.

Here's some gray stock on a Stock from the semi-highs:

Which is the same as a high number (ignore the contrast):

The Red Sox team card, a high number, also shows how Topps created "faux" series via

lagging the checklist information as they produced "preview" cards for the next series as the Fifties concluded.

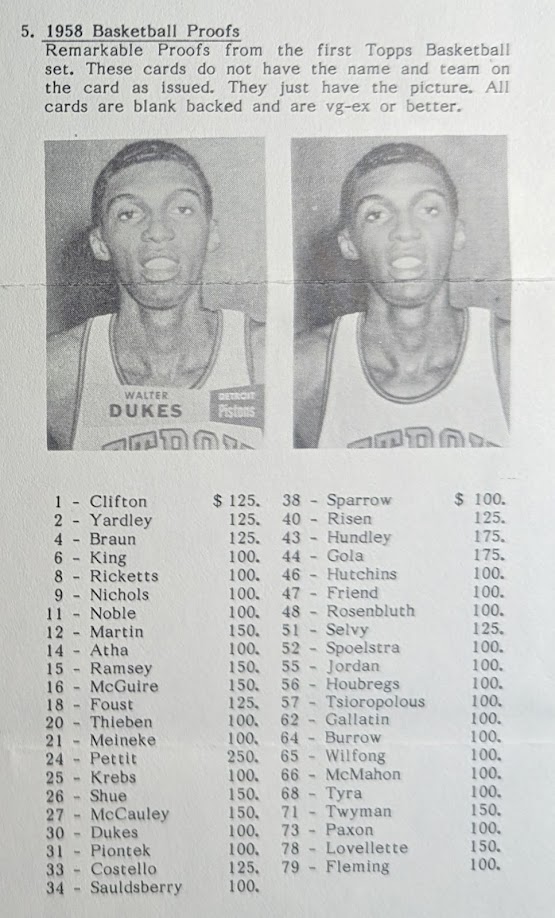

1961 saw the first traditional checklist cards, as major league baseball expanded for the first time in the 20th century, thus ending our tale today.