I've been going over some previously trod ground with a keener eye of late when it comes to Bowman and its various corporate reshufflings from 1951-56, much of it involving John Connelly, who assumed control then sold the company in fairly short order. One thing that I noticed doing this was the low figure offered by Bowman for its 1953 baseball card sales, which are described in some of their legal proceedings against Topps. Bowman's overall sales and those of their "baseball gum" look like they would have peaked in 1951 at $3,050,000 and $973,000 respectively (no prior figures are available but it makes sense given the large size of the 1951 set vs. 1950). There were probably some vending and cello sales as well but I doubt they approached even 5% of the baseball card sales figures overall.

In 1952, no doubt affected by the new Giant Size Baseball cards issued by Topps, sales trended down a little at $2,750,000 overall and $731,000 in respect of baseball gum. The decline in overall sales was $300,000 which seems almost entirely driven by their baseball cards dropping off by $242,000. Then in 1953 the bottom blew out with a thud. $2,140,000 in overall sales reflected only $301,000 worth of baseball product. The $610,000 drop in sales year over year is massive, almost 25%! Baseball gum was down $430,000 all on its own, so 70% of the loss in 1953 was related to that specific category.

It seems odd and the Bowman color cards were gorgeous of course, so why didn't they sell?

Well, I'm not sure they were marketed as they should have been. As it turned out, Bowman's parent company, Haelan Laboratories, mentioned in their annual report, which slightly refined some of the numbers from their lawsuit, that they lost $116,440 in 1952 due to "necessary and realistic adjustments preparatory to our entrance into newer and more profitable fields... inventory write-downs were substantial." The profit in 1952, despite better sales all around, was only $22,000, so there were two consecutive years of considerable "meh" going on for sure.

Cash flow woes may certainly have played a part in all of this since a write down occurs when your inventory drops below its book value. It seems to me then (and I am very much not a person who understands Generally Accepted Accounting Principles that well) that they couldn't sell their 1953 cards and the problem had a knock on effect throughout all their lines and businesses in 1953. Some of that may have been due to almost 30 percent of their baseball product being issued in black and white. I don't have the actual report, only a small excerpt, but assuming the write down represents what they could have sold at wholesale (58 to 60% of the retail price if they operated like Topps) and using the overall write down of $116,440, that projects to around $80,000 or so of unsold baseball gum inventory. And I'd say that's the minimum possible loss given the sales drop off for the baseball cards..

So that's something like 125,000 boxes of cards (over 5,000 cases, assuming five cent packs) that never sold and was probably the best case scenario. But it doesn't explain the enormity of their overall loss - remember the provided figures were representative of sales, not profits - or the loss on baseball gum in '53 and it's strange for sure. It may also explain how John Connelly (see last week's post) managed to get on the Haelan Laboratories board as it seems his business success was at least partially linked to theirs, especially in light of his plant burning down in January 1953. Maybe Bowman could not source enough shipping cartons, even as Connelly got his plant back up to speed?

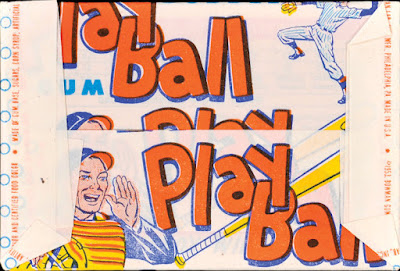

What I'm not seeing in any of these numbers how this inventory boondoggle is related to the oft-repeated story that production expenses manufacturing the color cards drove Bowman's demise, unless those losses extended to royalty payments. But there were certainly other issues going on that went well beyond their trading card lines. In fact, I think it bolsters my theory that they dropped the color cards in order to avoid paying royalties to Joe DiMaggio, their spokesman for the color set, shown on this five cent wrapper over at Wax Pack Gods:

I'm surprised to see Bowman using the old "Play Ball" name on cards we don't think of as Play Ball sets. Not to mention that none of their packaging seems to use the Bowman name other than perhaps in the small print.

ReplyDelete